28.5-27.08.2021 ① ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE

SHIFTERS

MARTA BOGDAŃSKA

KURATORKI:

Anna Bas, Karolina Wróblewska-Leśniak

Archiwum to nie tylko fizyczna przestrzeń, w której zbiera się i przechowuje materialne ślady wydarzeń, to także techniki archiwalne, tworzące funkcjonujące wersje pamięci. Sam termin „archiwum” pochodzi od greckiego słowa archeion, oznaczającego siedzibę władzy. Panujący nad archiwum decydują, jaką formę przyjmuje pamięć i czyja historia jest opowiadana. Archiwum ma moc interpretacji. Fotografie i materiały zebrane przez Martę Bogdańską w projekcie ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE są śladami istnienia innego archiwum, innej historii. Czy pytania: na co, na kogo patrzymy?, nie powinniśmy spróbować zastąpić pytaniem: co lub kto patrzy na nas? Stawiając się w miejscu zwierzęcia, spoglądamy na to, na co patrzyło zwierzę, ale czy widzimy to samo? Pytanie o status zwierzęcia jest być może jednym z najistotniejszych, które musimy sobie zadać. Francuski historyk Éric Baratay w Zwierzęcym punkcie widzenia podjął śmiałą próbę wyjścia poza wizję świata, w którego centrum znajduje się człowiek. Jego książka – będąca inspiracją Marty Bogdańskiej – skłania do zmiany sposobu czytania historycznych źródeł, do wydobywania z nich tego, co niedopowiedziane lub pomijane, do wczucia się w sytuację zwierzęcia. Chodzi o to, by „odwrócić pisanie, aby nie mówić o woźnicy, który powozi, wbijającym pikę pikadorze, leczącym weterynarzu, karmiącym panu ani o narzuconej pracy, zadanych razach, dostarczanym pożywieniu, udzielanej opiece, ale o koniu, który ciągnie, przeszytym byku, operowanej krowie, jedzącym psie…”.

ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE to próba opowiedzenia historii o nieantropocentrycznej konstrukcji, umieszczenia emocjonalnego i intelektualnego punktu widzenia po stronie postaci innych niż ludzkie. Przez stulecia zwierzęta były więzione w przedstawieniach ludzkiego autorstwa; przedstawieniach, które usprawiedliwiały używanie i wykorzystywanie zwierząt przez ludzi.

Wszelkie zaś zwierzę na ziemi i wszelkie ptactwo powietrzne niech się was boi i lęka. Wszystko, co się porusza na ziemi, i wszystkie ryby morskie zostały bowiem oddane wam we władanie. (Rdz 9, 2)

Co robi nasza historia ze zwierzęciem? Udomawia, ujeżdża, szkoli, tresuje, czyni posłusznym, dyscyplinuje, oswaja, formuje, żeby było pożyteczne, wydajne, dopasowane, łatwe w obsłudze, wytrzymałe i sprawdzające się w każdych warunkach. Kształtuje. Zmiennokształtność jest siłą zarówno destrukcyjną, jak i twórczą – w zależności od tego, jak ją wykorzystamy. O dokonanej przemianie zaświadcza wszczepiony obcy element, coś dodanego, co nie pochodzi z natury, lecz kultury. Paradoksalnie to, co naturalne, jest w hybrydycznym bycie postrzegane jako obce, a dodane jako swoje. Naśladuję, więc jestem?

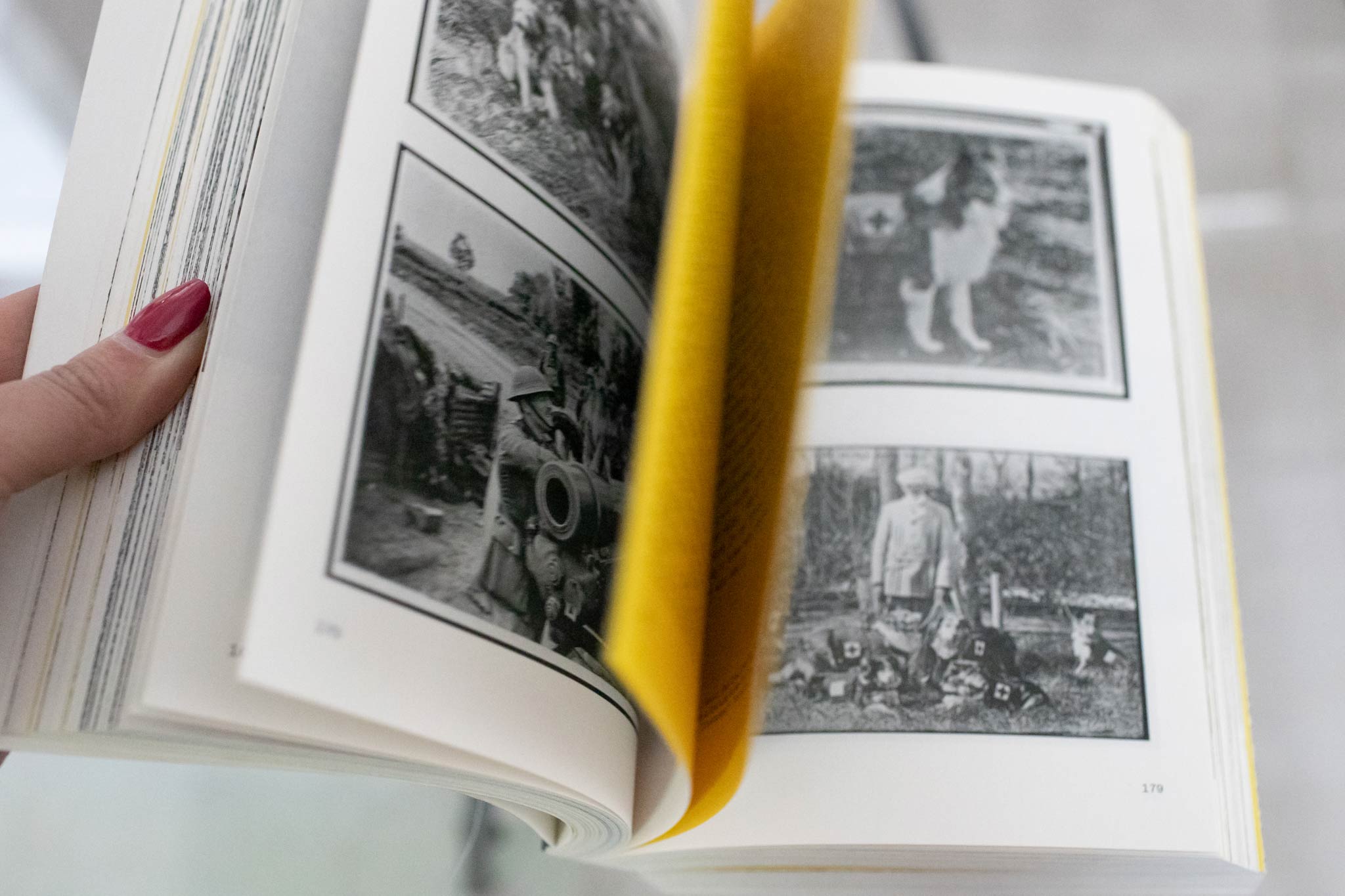

Poddawanie żywych istot procesowi transformacji to demonstracja władzy, wykorzystującej umiejętności i technologie w celu osiągnięcia konkretnej korzyści. Zwierzęta zostają wciągnięte w wydarzenia zwane historycznymi. Proces przekształcania polega na maskowaniu, wyposażaniu w rekwizyty, deformacji ciała, ale także na wpisaniu w pole nowych znaczeń. Zwierzęta przeobrażają się w śmiercionośną broń, siłę roboczą, mięso armatnie, barykadę, chwilową rozrywkę, w tajnego agenta wyposażonego w szpiegowską aparaturę, we współsprawców rzezi, w źródło ciepła i pożywienia. Patrząc na fotografie, spróbujmy nie szukać alegorii, symbolu, lecz zobaczyć czujące, doświadczające, działające istoty, które znalazły się w sytuacjach dla siebie niezrozumiałych i na które nie wyrażały zgody. Tożsamość podmiotu ludzkiego konstruowana jest w dużej mierze na zasadzie opozycji, które pozwalają nakreślić granicę oddzielającą swoje od obcego, znane od nieznanego, bezpieczne od niebezpiecznego, lepsze od gorszego. Tradycja przeciwstawiająca sobie człowieka i zwierzę to ta sama, która przeciwstawia sobie mężczyznę i kobietę, białego i niebiałego, oświeconego i barbarzyńcę, normatywnego i nienormatywnego, tożsamego i obcego. Zwierzę jest obcym, a obcy staje się też zwierzęciem. Słowa „zwierzę” używa się jako negatywnego epitetu nadawanego innemu, co pozwala na umniejszenie jego statusu, jego poniżenia, pogardzanie nim, odbieranie mu praw. Kiedy granica staje się przepaścią? Jacques Derrida określa jedną z krawędzi tej przepaści jako „krawędź antropocentrycznej subiektywności”1 . Poza ową krawędzią znalazła się heterogeniczna wielość bytów, którym odmawiamy prawa komunikacji, współudziału w historii. Nawet gdy niemożliwe jest uzyskanie prawdziwego dostępu do perspektywy zwierzęcia, to w archiwum innym niż oficjalne możemy odkryć pozostawione przez zwierzęta ślady, częściowo już zatarte, tropy

Anna Bas, Karolina Wróblewska-Leśniak

Archiwum to nie tylko fizyczna przestrzeń, w której zbiera się i przechowuje materialne ślady wydarzeń, to także techniki archiwalne, tworzące funkcjonujące wersje pamięci. Sam termin „archiwum” pochodzi od greckiego słowa archeion, oznaczającego siedzibę władzy. Panujący nad archiwum decydują, jaką formę przyjmuje pamięć i czyja historia jest opowiadana. Archiwum ma moc interpretacji. Fotografie i materiały zebrane przez Martę Bogdańską w projekcie ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE są śladami istnienia innego archiwum, innej historii. Czy pytania: na co, na kogo patrzymy?, nie powinniśmy spróbować zastąpić pytaniem: co lub kto patrzy na nas? Stawiając się w miejscu zwierzęcia, spoglądamy na to, na co patrzyło zwierzę, ale czy widzimy to samo? Pytanie o status zwierzęcia jest być może jednym z najistotniejszych, które musimy sobie zadać. Francuski historyk Éric Baratay w Zwierzęcym punkcie widzenia podjął śmiałą próbę wyjścia poza wizję świata, w którego centrum znajduje się człowiek. Jego książka – będąca inspiracją Marty Bogdańskiej – skłania do zmiany sposobu czytania historycznych źródeł, do wydobywania z nich tego, co niedopowiedziane lub pomijane, do wczucia się w sytuację zwierzęcia. Chodzi o to, by „odwrócić pisanie, aby nie mówić o woźnicy, który powozi, wbijającym pikę pikadorze, leczącym weterynarzu, karmiącym panu ani o narzuconej pracy, zadanych razach, dostarczanym pożywieniu, udzielanej opiece, ale o koniu, który ciągnie, przeszytym byku, operowanej krowie, jedzącym psie…”.

ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE to próba opowiedzenia historii o nieantropocentrycznej konstrukcji, umieszczenia emocjonalnego i intelektualnego punktu widzenia po stronie postaci innych niż ludzkie. Przez stulecia zwierzęta były więzione w przedstawieniach ludzkiego autorstwa; przedstawieniach, które usprawiedliwiały używanie i wykorzystywanie zwierząt przez ludzi.

Wszelkie zaś zwierzę na ziemi i wszelkie ptactwo powietrzne niech się was boi i lęka. Wszystko, co się porusza na ziemi, i wszystkie ryby morskie zostały bowiem oddane wam we władanie. (Rdz 9, 2)

Co robi nasza historia ze zwierzęciem? Udomawia, ujeżdża, szkoli, tresuje, czyni posłusznym, dyscyplinuje, oswaja, formuje, żeby było pożyteczne, wydajne, dopasowane, łatwe w obsłudze, wytrzymałe i sprawdzające się w każdych warunkach. Kształtuje. Zmiennokształtność jest siłą zarówno destrukcyjną, jak i twórczą – w zależności od tego, jak ją wykorzystamy. O dokonanej przemianie zaświadcza wszczepiony obcy element, coś dodanego, co nie pochodzi z natury, lecz kultury. Paradoksalnie to, co naturalne, jest w hybrydycznym bycie postrzegane jako obce, a dodane jako swoje. Naśladuję, więc jestem?

Poddawanie żywych istot procesowi transformacji to demonstracja władzy, wykorzystującej umiejętności i technologie w celu osiągnięcia konkretnej korzyści. Zwierzęta zostają wciągnięte w wydarzenia zwane historycznymi. Proces przekształcania polega na maskowaniu, wyposażaniu w rekwizyty, deformacji ciała, ale także na wpisaniu w pole nowych znaczeń. Zwierzęta przeobrażają się w śmiercionośną broń, siłę roboczą, mięso armatnie, barykadę, chwilową rozrywkę, w tajnego agenta wyposażonego w szpiegowską aparaturę, we współsprawców rzezi, w źródło ciepła i pożywienia. Patrząc na fotografie, spróbujmy nie szukać alegorii, symbolu, lecz zobaczyć czujące, doświadczające, działające istoty, które znalazły się w sytuacjach dla siebie niezrozumiałych i na które nie wyrażały zgody. Tożsamość podmiotu ludzkiego konstruowana jest w dużej mierze na zasadzie opozycji, które pozwalają nakreślić granicę oddzielającą swoje od obcego, znane od nieznanego, bezpieczne od niebezpiecznego, lepsze od gorszego. Tradycja przeciwstawiająca sobie człowieka i zwierzę to ta sama, która przeciwstawia sobie mężczyznę i kobietę, białego i niebiałego, oświeconego i barbarzyńcę, normatywnego i nienormatywnego, tożsamego i obcego. Zwierzę jest obcym, a obcy staje się też zwierzęciem. Słowa „zwierzę” używa się jako negatywnego epitetu nadawanego innemu, co pozwala na umniejszenie jego statusu, jego poniżenia, pogardzanie nim, odbieranie mu praw. Kiedy granica staje się przepaścią? Jacques Derrida określa jedną z krawędzi tej przepaści jako „krawędź antropocentrycznej subiektywności”1 . Poza ową krawędzią znalazła się heterogeniczna wielość bytów, którym odmawiamy prawa komunikacji, współudziału w historii. Nawet gdy niemożliwe jest uzyskanie prawdziwego dostępu do perspektywy zwierzęcia, to w archiwum innym niż oficjalne możemy odkryć pozostawione przez zwierzęta ślady, częściowo już zatarte, tropy

CURATORS:

Anna Bas, Karolina Wróblewska-Leśniak

The archive is not only a physical space wherein material traces of events are collected and stored, but also the archival techniques that generate functioning versions of memory. The term ‘archive’ is derived from the Greek word arkheion, meaning ‘seat of power.’ Those who control the archive decide what form memory will take and whose story will be told. The archive holds the power of interpretation. The photographs and materials collected by Marta Bogdańska for her SHIFTERS project are traces of the existence of other archives, other histories. Instead of asking, ‘What, and who, are we looking at?’ should not the question be: ‘What or who is looking at us?’ Putting ourselves in the position of the animal, we look at what the animal was looking at—but do we see the same thing? The question of the status of the animal is perhaps one of the most important questions we must ask ourselves. In The Animal Point of View: Another Version of the Story, the French historian Éric Baratay ambitiously seeks to transcend anthropocentric conceptions of the world. His book—the inspiration for Marta Bogdańska—pushes us to change the way we read historical sources: to extract from them the unsaid and the omitted while empathising with the plight of animals. The point is to ‘reverse the writing so as not to talk about the coachman driving, the picador stabbing, the veterinarian treating, the master feeding; nor about the work imposed, the blows delivered, the food provided, the care ministered; but about the horse straining, the bull stabbed, the cow operated on, the dog eating…’

SHIFTERS is an attempt to tell a story about a non-anthropocentric construction, reorienting the emotional and intellectual point of view to the side of the non-humans. For centuries, animals have been entrapped in representations authored by people; performances that justified the use and exploitation of animals by humans.

The fear and dread of you will fall on all the beasts of the earth, and on all the birds in the sky, on every creature that moves along the ground, and on all the fish in the sea; they are given into your hands. (Genesis 9:2)

What does our story do to the animal? It domesticates, breaks, trains, drills, makes obedient, disciplines, tames, moulds, so that the animal is useful, efficient, suitable, durable, low maintenance, weatherproof and able to be worked in all conditions. It shapes. Shapeshifting can be a destructive or a creative force, depending on how it is utilised. The transformation that has taken place is attested to by an implanted foreign element: something added that does not derive from nature, but from culture. Paradoxically, what is natural is treated as foreign in the hybrid, whereas natural is redefined as what we ourselves have inculcated.

I imitate, therefore I am?

To subject a living thing to transformation is a demonstration of power, using skills and technologies in order to achieve specific ends. Animals are drawn into events that are deemed historical. The transformation process involves masking, equipping with props, deformation of the body, and, in the process, the introduction of new planes of meaning. Animals are turned into lethal weapons, a workforce, cannon fodder, barricades, entertainment to pass the time, secret agents strapped with spy gear, accomplices in the slaughter, a source of heat and sustenance. Looking at the photographs, let us refrain from pointing out the allegorical and symbolic and see instead these sentient, aware, agential beings who found themselves involved in bewildering situations to which they did not give their consent.

The identity of the human subject is largely constructed on the basis of oppositions, which facilitate the demarcation of lines separating oneself from the other, the known from the unknown, safe from dangerous, better from worse. The tradition that juxtaposes man with animal is the same legacy that juxtaposes man with woman, White with non-White, enlightened with savage, normative with non-normative, alike with alien. As the animal is an other, so, too, does the other become an animal. The word ‘animal’ is assigned as a pejorative to the other in order to diminish their status, humiliate them, execrate them, strip them of their rights. When does the border become a precipice? Jacques Derrida terms one such precipice ‘the edge of an anthropocentric subjectivity.’1 Beyond that edge there is a heterogeneous multiplicity of beings to whom we deny the right of communication, of participation in history. Even if gaining true access to the animal’s perspective is out of reach, in a non-official archive we may discover—left by the animals, partially effaced—traces, tracks.

Anna Bas, Karolina Wróblewska-Leśniak

The archive is not only a physical space wherein material traces of events are collected and stored, but also the archival techniques that generate functioning versions of memory. The term ‘archive’ is derived from the Greek word arkheion, meaning ‘seat of power.’ Those who control the archive decide what form memory will take and whose story will be told. The archive holds the power of interpretation. The photographs and materials collected by Marta Bogdańska for her SHIFTERS project are traces of the existence of other archives, other histories. Instead of asking, ‘What, and who, are we looking at?’ should not the question be: ‘What or who is looking at us?’ Putting ourselves in the position of the animal, we look at what the animal was looking at—but do we see the same thing? The question of the status of the animal is perhaps one of the most important questions we must ask ourselves. In The Animal Point of View: Another Version of the Story, the French historian Éric Baratay ambitiously seeks to transcend anthropocentric conceptions of the world. His book—the inspiration for Marta Bogdańska—pushes us to change the way we read historical sources: to extract from them the unsaid and the omitted while empathising with the plight of animals. The point is to ‘reverse the writing so as not to talk about the coachman driving, the picador stabbing, the veterinarian treating, the master feeding; nor about the work imposed, the blows delivered, the food provided, the care ministered; but about the horse straining, the bull stabbed, the cow operated on, the dog eating…’

SHIFTERS is an attempt to tell a story about a non-anthropocentric construction, reorienting the emotional and intellectual point of view to the side of the non-humans. For centuries, animals have been entrapped in representations authored by people; performances that justified the use and exploitation of animals by humans.

The fear and dread of you will fall on all the beasts of the earth, and on all the birds in the sky, on every creature that moves along the ground, and on all the fish in the sea; they are given into your hands. (Genesis 9:2)

What does our story do to the animal? It domesticates, breaks, trains, drills, makes obedient, disciplines, tames, moulds, so that the animal is useful, efficient, suitable, durable, low maintenance, weatherproof and able to be worked in all conditions. It shapes. Shapeshifting can be a destructive or a creative force, depending on how it is utilised. The transformation that has taken place is attested to by an implanted foreign element: something added that does not derive from nature, but from culture. Paradoxically, what is natural is treated as foreign in the hybrid, whereas natural is redefined as what we ourselves have inculcated.

I imitate, therefore I am?

To subject a living thing to transformation is a demonstration of power, using skills and technologies in order to achieve specific ends. Animals are drawn into events that are deemed historical. The transformation process involves masking, equipping with props, deformation of the body, and, in the process, the introduction of new planes of meaning. Animals are turned into lethal weapons, a workforce, cannon fodder, barricades, entertainment to pass the time, secret agents strapped with spy gear, accomplices in the slaughter, a source of heat and sustenance. Looking at the photographs, let us refrain from pointing out the allegorical and symbolic and see instead these sentient, aware, agential beings who found themselves involved in bewildering situations to which they did not give their consent.

The identity of the human subject is largely constructed on the basis of oppositions, which facilitate the demarcation of lines separating oneself from the other, the known from the unknown, safe from dangerous, better from worse. The tradition that juxtaposes man with animal is the same legacy that juxtaposes man with woman, White with non-White, enlightened with savage, normative with non-normative, alike with alien. As the animal is an other, so, too, does the other become an animal. The word ‘animal’ is assigned as a pejorative to the other in order to diminish their status, humiliate them, execrate them, strip them of their rights. When does the border become a precipice? Jacques Derrida terms one such precipice ‘the edge of an anthropocentric subjectivity.’1 Beyond that edge there is a heterogeneous multiplicity of beings to whom we deny the right of communication, of participation in history. Even if gaining true access to the animal’s perspective is out of reach, in a non-official archive we may discover—left by the animals, partially effaced—traces, tracks.

MARTA BOGDAŃSKA

artystka wizualna, fotografka, menedżerka kultury, reżyserka dokumentu Next Sunday. Ukończyła filozofię na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. Studiowała z A. Vidokle w Homeworkspace Program organizowanym przez Ashkal Alwan w Bejrucie oraz gender; studies w Warszawie. Absolwentka Akademii Fotografii, Szkoły Patrzenia przy Instytucie Fotografii Fort oraz Instytutu Otwartego przy Teatrze Powszechnym w Warszawie. Realizowała międzynarodowe projekty artystyczne i kulturalne, m.in. w Libanie, gdzie mieszkała przez osiem lat. Należy do Archiwum Protestów Publicznych. Laureatka konkursu Talent Roku 2020. Prace Marty pokazywano na Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam 2020, Milano Design Film Festival 2020, BLICA – Pierwszym Biennale Sztuki w Libanie, Festiwalu TIFF we Wrocławiu, Art Market Budapest, Fotofestiwalu Łódź, Odessa Photo Days 2020, Encontros Da Imagem, Imago Lisboa, FIF BH – Międzynarodowym Festiwalu Fotografii w Brazylii, Festiwalu Fotograficznym OBSCURA w Malezji, Sursock Museum, Galerii Labirynt.

Jej książkę artystyczną SHIFTERS (ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE) nominowano do Kassel Dummy Award 2020, Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles 2020 oraz MACK First Book Award 2020.

artystka wizualna, fotografka, menedżerka kultury, reżyserka dokumentu Next Sunday. Ukończyła filozofię na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. Studiowała z A. Vidokle w Homeworkspace Program organizowanym przez Ashkal Alwan w Bejrucie oraz gender; studies w Warszawie. Absolwentka Akademii Fotografii, Szkoły Patrzenia przy Instytucie Fotografii Fort oraz Instytutu Otwartego przy Teatrze Powszechnym w Warszawie. Realizowała międzynarodowe projekty artystyczne i kulturalne, m.in. w Libanie, gdzie mieszkała przez osiem lat. Należy do Archiwum Protestów Publicznych. Laureatka konkursu Talent Roku 2020. Prace Marty pokazywano na Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam 2020, Milano Design Film Festival 2020, BLICA – Pierwszym Biennale Sztuki w Libanie, Festiwalu TIFF we Wrocławiu, Art Market Budapest, Fotofestiwalu Łódź, Odessa Photo Days 2020, Encontros Da Imagem, Imago Lisboa, FIF BH – Międzynarodowym Festiwalu Fotografii w Brazylii, Festiwalu Fotograficznym OBSCURA w Malezji, Sursock Museum, Galerii Labirynt.

Jej książkę artystyczną SHIFTERS (ZMIENNOKSZTAŁTNE) nominowano do Kassel Dummy Award 2020, Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles 2020 oraz MACK First Book Award 2020.

MARTA BOGDAŃSKA

is a visual artist, photographer, cultural manager, and filmmaker, including of the documentary Next Sunday. She studied philosophy and gender studies at the University of Warsaw, and with Anton Vidokle at the Home Workspace Program, organised by Ashkal Alwan in Beirut. She is a graduate of the Academy of Photography in Warsaw, the School of Looking at the Fort Institute of Photography, and the Open Institute at the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw. She has carried out international artistic and cultural projects, including in Lebanon, where she lived for eight years, and is a member of the Archive of Public Protests. She was the winner of the Pix.house Talent of the Year 2020 competition for her artist’s book Plaintext. Her works have been shown at the Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam, Milano Design Film Festival, BLICA – Lebanese International Biennale for Cinema and the Arts, TIFF Festival in Wrocław, Art Market Budapest, Fotofestiwal in Łódź, Odessa Photo Days, Encontros da Imagem in Braga, Imago Lisboa Photo Festival, FIF – International Festival of Photography of Belo Horizonte, OBSCURA Festival of Photography in Malaysia, the Sursock Museum in Beirut, and the Labyrinth Gallery in Lublin.

Her artist’s book SHIFTERS was nominated for the Kassel Dummy Award, the Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles, and the MACK First Book Award.

is a visual artist, photographer, cultural manager, and filmmaker, including of the documentary Next Sunday. She studied philosophy and gender studies at the University of Warsaw, and with Anton Vidokle at the Home Workspace Program, organised by Ashkal Alwan in Beirut. She is a graduate of the Academy of Photography in Warsaw, the School of Looking at the Fort Institute of Photography, and the Open Institute at the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw. She has carried out international artistic and cultural projects, including in Lebanon, where she lived for eight years, and is a member of the Archive of Public Protests. She was the winner of the Pix.house Talent of the Year 2020 competition for her artist’s book Plaintext. Her works have been shown at the Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam, Milano Design Film Festival, BLICA – Lebanese International Biennale for Cinema and the Arts, TIFF Festival in Wrocław, Art Market Budapest, Fotofestiwal in Łódź, Odessa Photo Days, Encontros da Imagem in Braga, Imago Lisboa Photo Festival, FIF – International Festival of Photography of Belo Horizonte, OBSCURA Festival of Photography in Malaysia, the Sursock Museum in Beirut, and the Labyrinth Gallery in Lublin.

Her artist’s book SHIFTERS was nominated for the Kassel Dummy Award, the Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles, and the MACK First Book Award.

SPACER WIRTUALNY

ORGANIZATOR WYSTAWY︎ORGANISERS:

Fundacja Sztuk Wizualnych sztukawizualna.org

Miesiąc Fotografii w Krakowie photomonth.com

PARTNERZY WYSTAWY︎PARTNERS:

Galeria ASP w Krakowie instagram/gaspkrk

Instytut Fotografii Fort instytutfotografiifort.org.pl

Współwydawca książki:

Landskorona Foto landskronafoto.org

ŹRÓDŁO︎SOURSE: photomonth.com

Fundacja Sztuk Wizualnych sztukawizualna.org

Miesiąc Fotografii w Krakowie photomonth.com

PARTNERZY WYSTAWY︎PARTNERS:

Galeria ASP w Krakowie instagram/gaspkrk

Instytut Fotografii Fort instytutfotografiifort.org.pl

Współwydawca książki:

Landskorona Foto landskronafoto.org

ŹRÓDŁO︎SOURSE: photomonth.com